Privilege is not a dirty word.

The move towards Mana Ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori.

Recognising the need to move towards Mana Ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori is a long awaited step in the right direction for education in Aotearoa. It’s exciting, and for many people – myself included – it is scary. Why? Because for many teachers, their experience of education in New Zealand – both as students, and as teachers – has been fundamentally ‘white’. We are good teachers, who want to do the best for our students, but because of New Zealand’s history of privileging the ‘white’ experience, there is a significant gap in our knowledge around te ao Māori.

The anxiety is real.

The lack of knowledge is a reflection of our privilege.

For white educators in Aotearoa, our own knowledge and experience has – up until recently – been reflected daily in our educational reality. We didn’t notice because it fit within our own narrative. Even when we ventured out into the unknown in an effort to be inclusive and take risks, we were still able to return to the safety of what we knew because it was the norm.

This is privilege – it is not a dirty word – it is just the truth.

While the focus on te ao Māori within education is a positive step, this is only one part of the kōrero that is needed to ensure equity for Māori and other non-white learners.

White privilege has been ingrained in our education system since its very existence in Aotearoa and as educators and school leaders, we need to be addressing the systemic ‘whiteness’ that is prevalent, irrespective of the anxiety it may cause.

The Oxford dictionary defines privilege as: a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group. It is no surprise that up until recently, education has consistently privileged the ‘culture and experience’ of ‘white middle-class students and their families (Angus, 2012) and in doing so, silenced the voices and experiences of the indigenous people of New Zealand – tangata whenua (Alton-Lee, 2017). As Choules (2007) highlights, ‘the key point about privilege is that it is ‘unearned’ and ‘arbitrary’; ‘an accident of birth (p. 472)’ – yet it still plays a dominant role in education today.

Why is it that we need to acknowledge this?

Because the problem with privilege is that those who have it and have benefited from it, tend to not understand the power of it. In fact, so ‘normalised’ have the structures and experiences of those with privilege become, that they are ignorant of the disadvantages faced by those without it (Angus, 2012) – going so far as to becoming resistant to accepting that there is a ‘structural advantage to being part of the dominant group (Choules, 2007)’.

Within an educational context, often the structural advantages afforded to the dominant power are so well hidden that advantages within the system are seen to be reflections of merit and effort rather than acknowledging they are a by-product of white privilege. As Angus highlights, ‘the attitudes, behaviours and characteristics of the [white] middle class have been allowed to define the norm,’ and this is particularly noticeable in education today.

While Choules (2007) acknowledges that those who have privilege, ‘do not act with the intention of maintaining systems of injustice (p 461),’ it cannot be ignored that ‘privilege exists in a symbiotic relationship with oppression (Angus, 2012),’ thereby having a detrimental effect on those who do not benefit.

Reports from the Ministry have suggested that schools adopt more culturally responsive practices yet they have acknoweldged that, ‘many principals were not implementing these practices widely,’ demonstrating that white settler colonialism remains present in schools across Aotearoa (Wylie et al, 2017). According to the OECD report (2016), just over 86% of school leaders identified as white, while the student population is becoming more diverse – resulting in a ‘significant cultural gap between school leaders and their students (Shiller, 2020)’.

There is a need for leaders to ‘self-reflect’ and ‘question where knowledge comes from (Hohepa, 2013),’ in order to truly understand the power of the dominant voice in their school – this is how they will learn to understand white privilege from an institutional perspective. As it stands, areas such as assessment, curriculum, systems and knowledge tend to prioritise a traditional (Eurocentric) way of doing things, while not acknowledging the harm that these processes have had on our non-white learners.

This is not a small issue. It is also not an issue that everybody has a responsibility to remedy. As a white educator in Aotearoa, I understand that I have a role in challenging the dominant narrative that has taken up space in our schools for far too long. I share this responsibility with many educators throughout Aotearoa – the difficulty is knowing where to start.

Challenging the narrative:

While acknowledging the impact that white privilege has had within education is important, it is wasted if we don’t take steps to mitigate its impact. So how can we do this?

- Change the coded language we use. Marginalised. Disadvantaged. Underserved. Underprivileged. All of these words have been used at schools I have worked in throughout Aotearoa to describe our ākonga and communities. I know that the intention was good. I know we thought we were helping. I know I was guilty of using them. As teachers, we want to do what we can to support our learners. However, despite having the best intentions, these words have an ‘underlying and critical meaning (DiAngelo, 2011)’ which works to reinforce racist narratives towards those who are often categorised within these groups – and often those students are not white. Racial coding is difficult to avoid in schools, but it acts as a signpost for stereotypes that have stigmatised our students for generations. This needs to change.

- Be honest about New Zealand’s history: According to the Ministry’s website, ‘Aotearoa New Zealand is on a journey to ensure that all ākonga in our schools and kura learn how our histories have shaped our present day lives (Ministry of Education, 2023a),’ and while this is a fantastic first step, a stronger effort needs to be made to ensure the past stories and experiences of Māori are acknowledged in all their truth, rather than downplaying the horrific violence and injustice that occurred. Tangible examples of this can be seen on The Ministry’s School Leavers Toolkit website, where references to the impacts of colonisation are truly sanitised: ‘When settlers arrived from Europe, many thought that they were better than the Māori already living here, and used this to justify some pretty awful things. Some of these ideas still affect Aotearoa New Zealand today (Ministry of Education, 2023b).’ No mention of the violence enacted toward Māori. No mention of how these inhumane acts have impacted Māori in particular today. Generational trauma and our violent colonial past have been glossed over completely. It’s time for us to own our history.

- Get comfortable with the uncomfortable: White fragility. Those words are enough to make the hairs on the back of people’s neck stand up. But we all know what it looks like: outward displays of emotion – argumentative, angry, disagreeable, silence or refusal to engage – when even a small amount of racial stress becomes ‘intolerable’ (DiAngelo, 2011). We need to stop this. We need to stop ignoring the complaints in the staffroom, the eye rolls, the under-our-breath commentary – and we need to listen. Dr Georgina Stewart (2020) talks about the need for white educators to get comfortable with the uncomfortable stating, ‘An extremely common reaction by Pākehā people in education is to take offense when a colleague or presenter raises uncomfortable aspects of Māori perspectives on things (p. 304).’ Reacting so overtly to issues of race works to keep the spotlight on the white narrative, while undermining the stories and perspectives of others – ultimately perpetuating the dominant voice (DiAngelo, 2011).

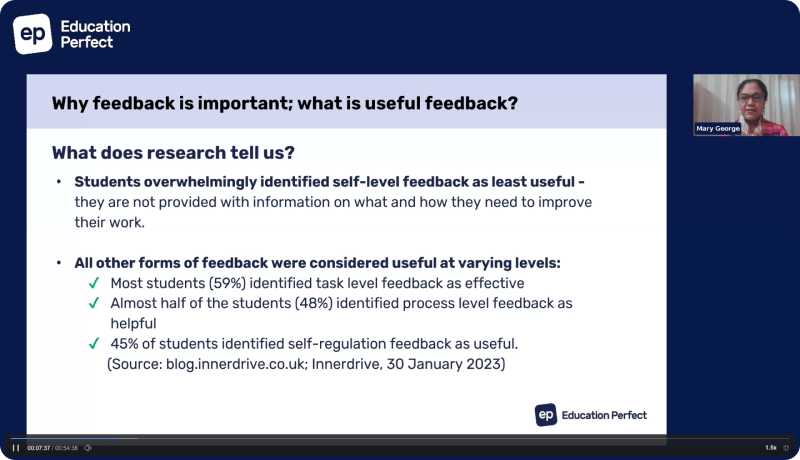

- Educate ourselves: Dr Georgina Tuari Stewart (2020) sums this up well in her article ‘A Typology of Pākehā “whiteness”’ (well worth the read), when she talks about the attributes of white allies who have done the work and shown a ‘willingness to invest the time required to read, think and expand one’s horizons of knowledge (p. 307).’ Teachers are all busy people. We know this. We know that the job goes well beyond timetabled classes: the sport, the hui, the planning and the whānau connection all take time. But if we make the effort to dig deep, to critically reflect on our own experiences and learn from them, the ripple effect for our kura and our ākonga will be that much greater.

Privilege is not a dirty word, and we need to move away from treating it like it is one. Acknowledging the power imbalance that has occurred in education is the right thing to do and it is long overdue. While many of the necessary ‘big picture’ changes lie out of our control as educators in the classroom, there are definitely opportunities for us to challenge the narrative. Only then will we truly be able to work towards Mana Ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori.

By Jodine Hardwicke

References:

● Alton-Lee, A (2017). ‘Walking the Talk’ matters in the use of evidence for transformative education. Invited paper for the International Bureau of Education – UNESCO Project: Rethinking and repositioning curriculum in the 21st century: A global paradigm shift. Evidence, Data and Knowledge, Ministry of Education, Wellington: New Zealand

● Angus, L. (2012). Teaching within and against the circle of privilege: reforming teachers, reforming schools. Journal of Education Policy, 27(2), 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2011.598240

● Choules, K. (2007). The Shifting Sands of Social Justice Discourse: From Situating the Problem with “Them,” to Situating it with “Us.” The Review of Education/pedagogy/cultural Studies, 29(5), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714410701566348

● Hohepa, M. K. (2013). Educational Leadership and Indigeneity: Doing Things the Same, Differently. American Journal of Education, 119(4), 617–631. https://doi.org/10.1086/670964

● Ministry of Education. (2023) Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories and Te Takanga o Te Wā. Retrieved from: https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/changes-in-education/aotearoa-new-zealands-histories-and-te-takanga-o-te-wa/

● Ministry of Education. (2023). Racism and other forms of Discrimination: Understanding and challenging it in our daily lives. Retrieved from: https://school-leavers-toolkit.education.govt.nz/en/taking-care-of-myself-and-others/racism-and-other-forms-of-discrimination/

● OECD. (2016) Improving school leadership: Country background report for New Zealand, Improving School Leadership Activity Education and Training Policy Division. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/edu/schoolleadership.

● Shiller, J. T. (2020). Honoring the Treaty: School Leaders’ Embrace of Indigenous Concepts to Practice Culturally Sustaining Leadership in Aotearoa Aotearoa is the Indigenous name for New Zealand. Journal of School Leadership, 30(6), 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052684620951735

● Stewart, G. (2020). A typology of Pākehā “Whiteness” in education. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 42(4), 296-310

- Wylie, C., McDowell, S., Feral, H., Felgate, R., & Visser, H. (2017). Teaching Practices, school practises and principal leadership: The first national picture 2017. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.