Rethinking Assessment

Should we still be talking about assessment and testing of our students during remote learning? Are we still applying the same expectations and rules for our students in the completion of assessment whilst they are submitting work online?

As more and more schools around the globe consider the prospect of students continuing remote learning until June, I have seen many teachers and school management across a range of social media platforms asking – what about assessment and reporting? How do I test my students and know that they are not cheating or being dishonest? How can I still administer a test under test-conditions? But the more posts and discussions I read about this; I am starting to wonder if we are asking the wrong questions, or if there are better questions to ask. Could we more usefully ask – What is the primary purpose assessment serves?

Why do we assess?

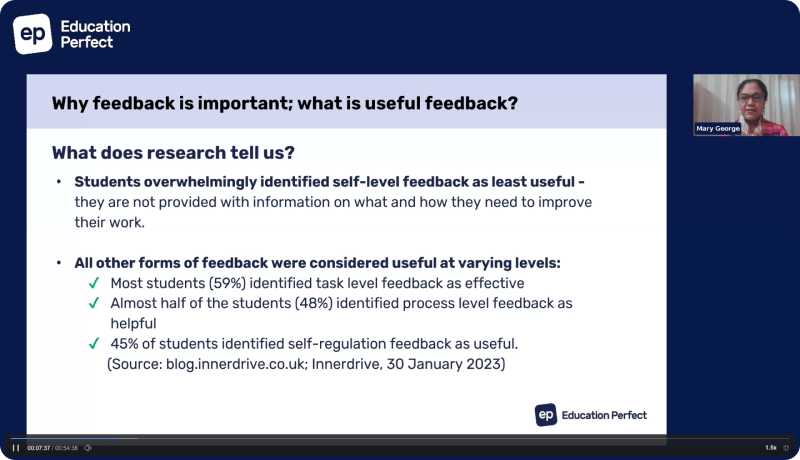

It is a simple question, with a well-known answer – teachers and schools use assessment and student performance to guide the learning process. Assessment is an integral part of education. It gives us clarity about our students’ understanding and it provides us with the opportunity to give meaningful feedback, to ensure continued learning and student development. The outcome of assessments encourages teachers to be reflective in their practice and to make critical decisions about whether educational goals and standards are being met.

In a typical classroom environment, we commonly used two types of assessment to measure the achievements of our students – summative and formative assessment.

Summative assessment gives teachers a summation of how effective or successful students are during a specific task or period of time. We use tasks such as tests and quizzes to provide a measure of students’ capabilities and their level of success.

Formative assessment is sometimes referred to as assessment as learning (Broadfoot et al., 2002). The goal of formative assessment is reflective and is designed to help students identify strengths and weaknesses, and target areas that need work. These tasks are an opportunity to not only give teachers data around which students are struggling but also allow for students to be given timely and “learner-centric” feedback in order to adjust and move their learning forward (Crockett et al., 2017, p11).

However, in an online environment, should we still be applying the same practices?

Summative assessment, such as online surveys, tests and quizzes, can be very useful in giving teachers a quick snapshot of where their students are at. It can help inform the direction of next week’s lessons and can be the data needed to start important dialogues with students or parents about areas of strength and weakness. Summative assessment is a useful evaluative tool of students’ learning at the end of an instructional unit.

However, without true testing conditions, teachers may question the validity of the data. Online testing may be felt as inadequate to measure students’ true understanding in these unique circumstances. What happens if my students are being dishonest?

In attempting to answer this, I would encourage teachers to consider two questions;

1. What is the purpose of the task?

As a Head of Department, I would ask this a lot of my colleagues and faculty staff whenever they wrote a new piece of assessment. What type of data are you trying to collect with this task? What are the objectives? What do you want your students to be able to demonstrate?

If the purpose of the task is to collect a snapshot of the student’s ability to demonstrate their understanding of content, facts and skills under a timed condition – then a test would be one tool that could allow for this. And there are many different programs, online tools and applications that allow for schools to administer such assessments in the online environment. I have seen many teachers post useful “hacks” or suggestions about how to replicate testing conditions similar to that of a classroom. However, “summative assessments provided no opportunity or responsibility for learning improvement. It is a judgement and it is final” (Crockett et al., 2017, p.3). Therefore, it is useful to consider, is that what you really want?

There are other ways to ask students to demonstrate their understanding, which do not rely on strict testing conditions and may even encourage students to use the resources available to them. With a wealth of online information available to students with a simple keystroke, should we still be asking our students to memorise and regurgitate information under testing conditions? Even before COVID-19, there was a tension between existing assessment policies and the demand to assess 21st century skills. This tension is further strained as we attempt to transpose digital technologies onto an existing framework of assessment. It is problematic because the “measures have been constructed using pedagogical beliefs which predate the digital age” (Heppell, 1999 in Starkey, 2016). No longer is it just about ‘knowing stuff’.

Instead, reconsider the purpose of the assessment task. Our assessments should be deliberate and purposeful. As the environment in which students are completing these assessments has changed, so too should our assessments evolve.

Instead of trying to recreate test conditions, let’s allow students to have access to their books and the internet. We shouldn’t be asking questions in our assessments where they can simply google the answer. Open-book tests are an opportunity to allow for students to focus on the quality of their answers rather then “what is the correct response”. It is an opportunity for teachers to focus on the skills of media literacy, effective communication and develop students as critical consumers of Google. If students have a good understanding of the content, facts and theory, they would be able to write meaningful and reflective answers. Those who do not have an understanding would struggle to apply this knowledge regardless of whether they have access to the internet or not. We should instead write tests and assessments which are open ended and ask students to evaluate, critique or design. And it is okay to spend some time teaching our students how to answer such questions. Much like we could not expect our students to be able to use a new maths skill without teaching them first, we can’t expect them to suddenly be able to answer these new style of questions.

Once the purpose of the task has been clarified, regardless of whether it is formative or summative, teachers are still asking about academic honesty.

2. How do you maintain or build trust with your students in the classroom – are you creating opportunities for this trust to be nurtured whilst online?

Many teachers do this automatically in our classrooms. The building of meaningful relationships with our students comes naturally to us. When we take the time to listen to our students, when we ask them meaningful questions, advocate for them and acknowledge them – we are building this trust. Pre-COVID-19, I doubt many of you asked the questions, how do I ensure my students are being honest? How do I trust that my students are doing the right thing with their assessments? So why are we asking this so much now and what are we doing to regain this level of trust that we had back in the classroom?

Simply put, the same rules apply when it comes to building and maintaining trust, whether your students are in your real-world or virtual classroom. We should continue to be tolerant and understanding, we should continue to respond intentionally, we should continue to be consistent and acknowledge their feelings. And lastly, we should continue to speak honestly and perhaps even have a group discussion about your concerns around the importance of academic credibility and professional honesty. By taking the time to create unique opportunities online to maintain this trust, then we should be able to restore the same level of faith we originally had in the work ethic of our students.

With a clearer understanding of the assessment purpose and re-establishing trust with our students, online assessment need not be an area of stress or concern for educators. Instead it can go back to its primary function of providing focused feedback and evaluation for both teachers and students.