Re-shaping assessments in the digital age

Increasingly we are using digital technologies to assess. If a student is operating in a digital space day to day, it makes sense that their assessment should mirror that. But what about students who don’t have access to devices? Are we widening the gap?

I’d argue that there is tension between existing assessment policy and the demand to assess 21st century skills. Transposing digital technologies onto an existing framework of assessment is problematic because the “measures have been constructed using pedagogical beliefs which predate the digital age” (Heppell, 1999 in Starkey, 2016). No longer is it just about ‘knowing stuff’. We are equipping students with vital interpersonal skills such as negotiation, collaboration, and problem solving. Additionally, students are learning media literacy and how to sift through and critically analyse information. Is it possible to assess these skills? Is there a better way to test the thinking behind decisions? Rarely do we work in isolation, without collaboration or access to resources. Why are we demanding our students do the same?

Let’s take Languages in New Zealand as an example. Listening and reading examinations are the traditional image of an assessment: standardised across New Zealand, static, one-off, and closed-book conditions. However, there have been efforts to infuse technology into these assessments. Since 2015, various languages have been involved in online assessment pilots or trials.

When evaluated against the Substitution Augmentation Modification Redefinition (SAMR) Model (Puentedura, 2014), the reading examination represents ‘substitution’. The assessment paper has simply been transposed onto the screen, with no functional change. However, the listening assessment has undergone ‘augmentation’. The key difference when compared to a pen and paper examination is that students have full agency over audio playback. What would a redefined listening assessment look like?

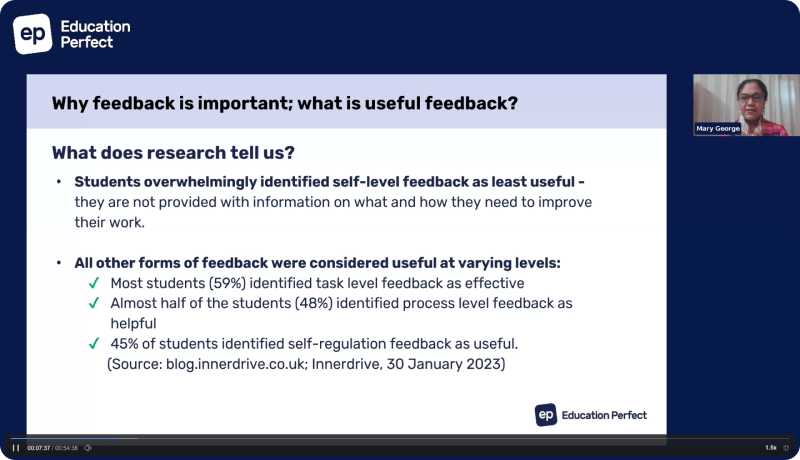

I developed a Language Acquisition Assessment Framework as part of my Master’s study. Drawing inspiration from Siemen’s (2004) connectivist principles and Starkey’s (2011) Digital Age Learning Matrix I proposed three internal assessments: Interact, Writing, and Viewing. As is current practice in New Zealand, the assessments are a collection of ongoing and authentic evidence of student progress. Feedback plays a crucial role in this framework and students receive it from various sources: self-reflection on their task, peer or foreign language peer, and from their teacher. I share it with you now to spark thought about how we could assess languages – and other subjects – in the digital age.

While we may not be able to change formal assessments, perhaps it is possible to draw out some elements to inform ongoing formative assessments. How can students share their work and establish connections with others to develop their understanding and create meaning? How is self and peer review integrated into assessment? How do you incorporate technology into existing assessments?

It comes down to what we value as educators – is it content knowledge, the ability to seek out and make sense of information, the sharing of knowledge, or a blend of it all?